List: How Ghanaian Muslims are imitating non-Muslim customs

Ghana is a secular state with a population of over 30 million, where one out of every five Ghanaians is a Muslim.

The disproportion in population size means the Muslim culture in Ghana is less dominant and largely influenced by the Ghanaian culture.

The Ghanaian culture is generally interwoven with African traditions, Christianity as the country’s dominant religion and Western culture by virtue of foreign media influence and colonisation.

The Islamic culture in Ghana therefore, has, over the years, evolved in many aspects, causing a fear of bid’a (religious innovation) among scholars.

Through socialisation, Muslims exchange ideas through interaction and adopt other people’s way of doing things.

In instances where people do embrace the Islamic religion, they do not entirely abandon their Ghanaian customs or social network for the sake of the new religion.

It is as though the prophet (peace be upon him) knew about the Ghanaian Muslim situation when he warned his followers against the imitation of cultures of certain religions and civilisations.

As narrated by Abu Sa`id: The Prophet (ﷺ) said, “You will follow the wrong ways of your predecessors so completely and literally that if they should go into the hole of a mastigure, you too will go there.

“We said, “O Allah’s Messenger (ﷺ)! Do you mean the Jews and the Christians?” He replied, “Who else?” (Meaning, of course, the Jews and the Christians.) Sahih al-Bukhari 3456

Also narrated by Abdullah ibn Umar: The Prophet (ﷺ) said, He who copies any people is one of them. Abu Dawood Hadith (4031)

After examining these hadith (teachings of the prophet), we take a closer look at some non-Muslim cultures that Muslims in Ghana are imitating and gradually embracing as part of everyday Muslim life.

In this Article

1. Adoption of Husband’s Surnames:

Islam does not encourage the changing of names after marriage, as the prophet (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) has classified it as an act of disbelief. He warned against attributing yourself to someone who is not your father.

He also said that “Whoever claims to belong to a people when he has nothing to do with them, let him take his place in Hell.” Al-Bukhari (3508) and Muslim (61).

The culture of women dropping their fathers’ names for that of their husbands or, in some cases, adding the family names of husbands is an ancient practice deeply rooted in patriarchal dominance.

For example, in many ancient societies, such as those in Greece and Rome, family lineage and inheritance were traced through the male line.

Women were often considered part of their husband’s household and adopted his name as a sign of that union.

During the mediaeval period in Europe, marriage often signified the transfer of women from one male guardian (father) to another (husband), and so taking the husband’s name symbolised this transition and reinforced patriarchal structures.

It was for these reasons that men feared for the survival of their lineage (the end of the family name) should they give birth to only daughters.

Unlike men, women who adopt their husbands’ names also struggle to maintain permanent identities, as they are required to change surnames anytime they remarry or divorce their spouses.

Despite its abhorrence in Islam, the practice has been magnified to appear enticing to some Ghanaian Muslim women.

The temptation to change surnames gets higher for those who marry into affluent families and would want to be recognised as members of such families.

2. Wearing of wedding ring:

It must be established that Islam is generally not against the wearing of rings, especially when it follows the conventional rules, such as men are not supposed to wear gold rings, men are exempted from wearing rings on the middle and index fingers, and rings should not be worn as amulets.

There is also nothing wrong with married Muslim couples surprising their spouses with rings or any other ornament for that matter as gifts.

There is, however, an objection when the wearing of the ring has a particular intention (showing off) and is seeking to imitate a tradition of a certain group of persons (Christians) whom the prophet has warned Muslims against.

Though lacking scriptural evidence, the wearing of a ring on the fourth digit finger has been synonymous with Christian marriages.

Christian couples in Ghana under the supervision of their cleric would fix a ring on the finger of their spouse while they exchange marital vows.

After the ceremony, the couples are to be seen wearing these rings for the rest of their lives (until death do them part) or divorce each other.

Some anchored the practice on a belief (proven to be untrue) that a vein ran directly from the fourth finger of the left hand to the heart, named the Vena Amoris, or “vein of love”.

This belief contributed to the tradition of wearing the wedding ring on that specific finger as a symbol of eternal love and commitment.

Unfortunately, some Muslims have adopted this practice. Some common reasons attributed to the practice are to ward off unwelcome attention from the other sex due to their marital status.

3. Memorial Service:

Death is inevitable, and mourning the dead is an indispensable feature of the Muslim culture. The mourning of the dead is, however, not expected to exceed three days and, in the case of a widow, not go beyond four months and ten days, as directed by the prophet in a hadith (Sahih al-Bukhari 5339).

In the Ghanaian culture, however, most ethnic groups, such as the Ashantis, Fantis and Gadangbe, extend the mourning period for relatives beyond three days.

These extension periods for mourning take the form of a one-week memorial service, a 40-day celebration, a one-year anniversary and beyond.

This is generally underpinned by the belief that at various stages the dead go through a transitioning period.

Over the years, these customs have caught up with some Muslims who, in one way or another, hold memorial services at various periods through special prayers held in honour of the death.

During such occasions, resources are expended by relatives to prepare food and share it, buy items for free distribution, and give money to Muslim clerics for prayers and Quran recitation.

4. Cutting the cake:

Cake is delicious. But like the history of many other non-Muslim customs, it is rooted in superstition and paganism.

Anthropologists trace the origin of cake cutting to ancient Greece, where they would light candles on cakes made of flour, honey, and nuts to honour Artemis, the goddess of the moon and the hunt.

The cakes were rounded to represent the moon, and the candles were lit to make it glow. The smoke from the candles was thought to carry wishes and prayers to the gods.

Since then, the practice of cutting cakes has permeated eras and cultures. It has become a symbolic act in many celebrations, such as weddings, birthdays, and anniversaries.

For the Ghanaian Muslim, the cutting of cakes during occasions is fast becoming a cultural fever.

The religious rhetoric antagonising the practice and the cultural shock that greeted the infusion of cake cutting into Muslim events such as nikkah (marriage ceremony) have gradually disappeared.

5. Birthday celebration:

The marking of one’s date of birth on an annual basis is a practice that dates back to hundreds of centuries ago.

Historians attribute the origin of birthday celebrations to early 3,000 BCE, where Egyptians celebrated the pharaoh’s coronation day as “the birthday of a god”.

In some pagan cultures, it is believed that evil spirits visited on birthdays; hence the need to gather during the celebration and make noise to protect one from the evil eye.

The current tradition of celebrating birthdays with a round cake full of candles came from the 18th-century German tradition called Kinderfeste.

Each candle is said to represent each year of a person’s life — plus one additional candle in the centre to represent the hope of another year.

Despite being deeply rooted in paganism, birthday celebrations have found expression in Muslim cultures worldwide.

In Ghana, the issue of birthday celebration for Muslims has become a controversial and sometimes sensitive matter to discuss.

It has taken a sectarian twist where one sect sees it to be an imitation of non-Muslims, while others regard it as an act of showing personal appreciation to Allah and reverence for religious figures.

The participation of senior clerics in birthday celebrations and the ensuing disagreement has given currency to the practice that could not be explicitly traced to the teachings of Islam.

6. Crossover into the new year:

With the introduction of the Julian calendar in 46 BCE, Julius Caesar, the ruler of Rome, declared January 1st as the start of the new year, honouring Janus, the Roman god of beginnings, endings, and transitions.

With his two faces, Janus was said to look back at the past and forward to the future, a perfect symbolism for New Year’s Eve.

The Romans celebrated the new year with parties, feasts, and sacrifices to Janus. They also exchanged gifts, such as coins and branches from sacred trees, as tokens of good fortune.

Over time, the new year celebration has become a religious festivity in Christendom where Christians hold religious ceremonies called “31st watch night” services to usher in the new year.

They gather on the eve of the new year, thus December 31, to pray until midnight with the hope of a better year that begins with the month of January.

Some also make merry on January 1 by visiting beaches, feasting and making wishes.

Even though Islam has a lunar calendar which has Muharram as the first month of the year, some Ghanaian Muslims participate in the new year ritual through merry-making, making wishes or holding crossover ceremonies in the form of special prayers or Quran recitation with the hope of glad tidings in the coming year.

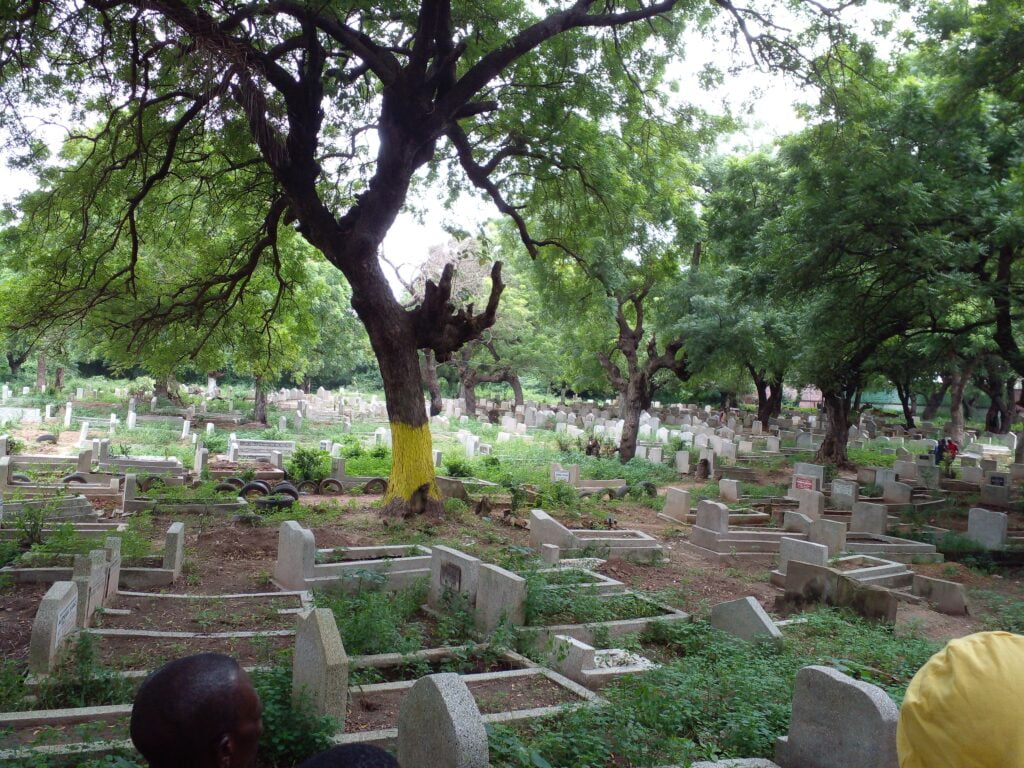

7. Grave Decoration:

A long-held custom of non-Muslims in Ghana has been the construction and decoration of graves with befitting monoliths and gravestones that reflect somberness and respect for the dead at cemeteries.

It must be said that this practice largely contradicts the doctrine of Islam as recorded in Jami` at-Tirmidhi 1052 and narrated by Jabir: “The Messenger of Allah prohibited plastering graves, writing on them, building over them, and treading on them.”

While some Muslims do well to keep the graveyard in accordance with this teaching of the prophet, the sight of graves erected with building blocks in Ghanaian Muslim cemeteries is not uncommon.

Others take it a step further to decorate them with writings such as Qur’anic verses, tributes, and names and dates of death, as done by the non-Muslims.

Join our whatsapp channel and Google News platform for all the latest updates.

For news coverage, article publication, and advertisement, send an email to ghanaianminaret@gmail.com or reach us via whatsapp, telegram or phone call on +233266666773.